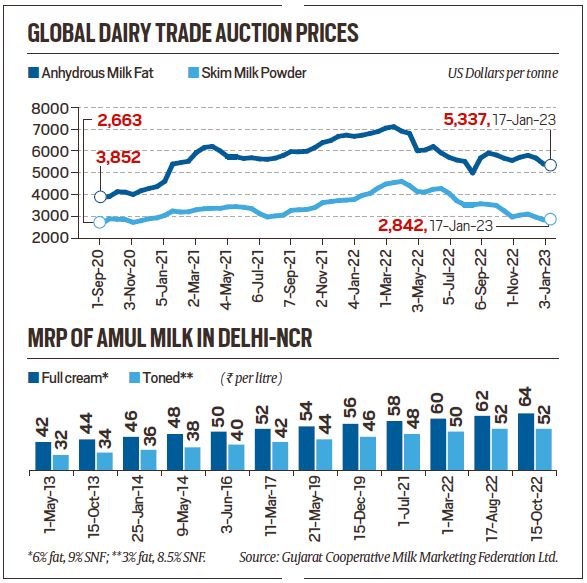

Within the last year, the Gujarat Co-operative Milk Marketing Federation has raised the maximum retail price (MRP) of its Amul brand full-cream milk (containing 6% fat and 9% SNF or solids-not-fat) in Delhi from Rs 58 to Rs 64 per litre. The National Dairy Development Board (NDDB)-owned Mother Dairy went further — from Rs 57 to Rs 66 per litre — between March 5 and December 27, 2022.

The last time milk prices went up by Rs 8/litre was between April-end 2013 and May 2014. From the table, it can be seen that the MRP rise in Amul milk wasn’t very significant after May 2014, when the Narendra Modi government came to power. It rose by just Rs 10/litre over almost eight years until February 2022.

Since then, prices have rocketed — and more for full-cream milk. The MRP revision in toned milk (3% fat and 8.5% SNF) by Mother Dairy has been only Rs 6 per litre (from Rs 47 to Rs 53), as against Rs 9 for full cream.

What explains this recent inflation?

There are multiple factors.

The most important probably has to do with the crash in prices following the Covid-induced lockdowns, which forced the closure of hotels, restaurants, canteens and sweetshops, apart from cancellation of weddings and other public functions. The demand destruction led dairies to slash procurement prices of cow milk (with 3.5% fat and 8.5% SNF) to Rs 18-20 per litre during April-July 2020 and that of buffalo milk (6.5% fat and 9% SNF) to Rs 30-32. This was accompanied by ex-factory prices of skim milk powder (SMP) collapsing to Rs 140-150 per kg, along with Rs 200-225/kg for cow butter and Rs 280-290/kg for ghee.

Farmers responded first by shrinking — or at least not expanding — the size of their herds, as milk prices would not cover the cost of feeding and maintaining the animals. Two, they underfed them — particularly the calves and the pregnant/ dry cattle not giving milk.

A newborn crossbred typically reaches puberty and is ready for insemination in 15-18 months. Adding 9-10 months of pregnancy, it will deliver and start lactating after 24-28 months. The age of first calving in buffaloes is higher, at 36-48 months.

The calves that were underfed during the lockdown — which extended past the second Covid wave until June 2021 and beyond — are today’s cows. Most of them, even if they have survived, would be poor milkers. This is evidenced by dairies across India reporting lower milk procurement, with the year-on-year drop up to 15-20% for the cooperative federations in Karnataka and Tamil Nadu. The same dairies that were refusing to buy from farmers in 2020-21 are at present paying Rs 37-38/litre for cow milk and Rs 54-56/litre for buffalo milk.

Is the legacy of underfed animals the only reason?

There are others too, both on the supply and demand fronts.

On the supply side, the average cost of cattle feed spiked from Rs 16-17 per kg in 2020-21 to Rs 22-23 by mid-2022, on the back of more expensive ingredients such as cotton-seed, rapeseed and groundnut extractions, soyabean meal, maize, de-oiled rice bran and molasses.

Availability of straw (particularly wheat, due to a poor 2021-22 crop) and fodder (because of near-incessant rains, especially in the South, from October-December 2021 through 2022, which did not allow the grass to fully come out) has also been an issue. On top of these came the outbreak of lumpy skin disease among cattle in July-September 2022, and seemingly impacted milk output further.

On the demand side, the lifting of lockdown restrictions and revival of economic activity from late-2021 coincided precisely with the building up of supply pressures. This was exacerbated by India exporting about 33,017 tonnes of milk fat worth Rs 1,281.15 crore in 2021-22 and 13,360 tonnes (Rs 664.82 crore) during April-November 2022, against a mere 15,600 tonnes (Rs 717.17 crore) in 2020-21. Higher exports of butter, ghee, and anhydrous milk fat, enabled by soaring international prices, have added to the domestic shortage — and as noted earlier, full cream milk has become dearer, with branded ghee and butter also disappearing from store shelves.

What’s the current situation and the future outlook?

In contrast to the 2020 lows, ex-factory per-kg realisations are now at Rs 305-315 for cow SMP, Rs 340-plus for buffalo SMP, Rs 425-430 for cow butter, and Rs 520-525 for ghee. “Milk shortfall is mainly in the South; it is better in Maharashtra. Even in the northern buffalo belt, supply hasn’t picked up as much as one would expect for the flush season,” said Ganesan Palaniappan, a leading Chennai-based dairy commodities trader.

But worse could lie ahead. The calving season (“flush”) for animals, when more milk flows from their udders, generally begins from September. That’s the time temperature and humidity levels dip, alongside improved fodder-cum-straw availability from the monsoon rain and harvesting of the kharif crop. The calvings peak in the winter and continue until March-April before the onset of summer.

The “flush” months are also when dairies convert the surplus milk that they procure into SMP, butter, and fat. Those, in turn, are used for reconstitution during the “lean” summer season, when the animals produce less, even as demand for curd, lassi, and ice cream surges.

What can the government do now?

A shortage of milk, more specifically fat, is a concern at this point when dairies would ordinarily be building up stocks for the summer. Since that’s not happening, it makes sense to allow duty-free imports of butter oil and SMP. The most recent price of $5,337 per tonne (Rs 435/kg) for anhydrous milk fat at New Zealand’s Global Dairy Trade fortnightly auction works out to below the corresponding domestic rate of Rs 520-525/kg. This wasn’t the case in March 2022, when global prices had topped $7,100 per tonne (see chart).

Butter fat imports currently attract 40% duty. For SMP imports, it is 15% up to 10,000 tonnes per year and 60% for quantities beyond that. The government can permit NDDB to import fat and SMP at zero duty for building up a buffer stock necessary for the summer, when milk supplies will dry up in the normal course. Domestic production should hopefully recover by the next “flush” season, when farmers would be enthused enough to milk more animals that have no dearth of feed or fodder.