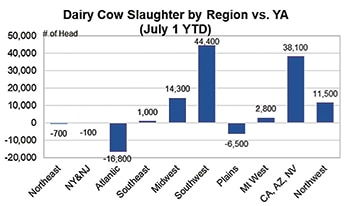

Dairy prices have fallen to levels not imagined several months ago, which have pulled milk prices lower. Class III milk prices are at the lowest level since Q2 2020 when COVID created havoc with dairy supply chains. Milk checks in some areas of the country are well below the cost of production, with higher culling rates seen in the Southwest and California so far this year. Dairy farms in those areas tend to purchase more of their feed, and with high feed costs in the last year, margins have been hit by both higher costs and lower milk prices. Areas in other parts of the country where farms raise more of their own feed have seen far lower culling rates.

While headlines point to dire farm financial conditions, the actual situation is more nuanced. This is not to say there aren’t farms struggling to survive, as pain is definitely being felt in some regions, but cow numbers have not seen much contraction yet this year. While modest declines are expected over the next several months, it is important to understand how factors other than milk price are impacting the supply and demand balance in dairy.

First, while we talk $15 Class III milk, this is at 3.5% butterfat and 2.99% true protein. Over the years, the average component levels have increased to 4.09% in 2022. Using the five-year average butterfat price of $2.38 per pound, that adds $1.40 per hundredweight to the milk price. For protein, milk with a test of 3.2% yields an extra $0.55 per hundredweight using the five-year average price of $2.65 per pound. Now that $15 milk is $17 at test — not great, but less dire than initially thought.

Next are the benefits of several risk management tools. Over 70% of the dairy farms in the country are enrolled in the Dairy Margin Coverage (DMC) program. For a farm that produces the limit of 5 million pounds per year, or around 225 cows, and is signed up for maximum coverage, they could collect nearly $150,000 this year. In fact, a comment was recently made that for some farms, if it were not for DMC payments, they would not be able to pay their bills. In addition, many large farms use Dairy Revenue Protection (DRP) insurance to floor prices for milk. A recent Ever.Ag report estimated nearly 80% of milk is covered by either DRP or DMC in Q3. Therefore, the market signal to reduce production is muted by these payments. This is positive for farm balance sheets, but the unintended consequence is to delay a recovery in prices as farms keep producing milk.

Another recent change in dairy farm economics is energy revenue. Around 20% of the cows in the U.S. are on farms with methane digesters. For a 3,500-cow dairy at $100/cow/year, this is close to $0.40 per hundredweight. These farms are also locked into a contract to supply manure from a set number of cows, so downsizing is not an option. As more digesters are installed on farms for gas and electricity production, the new revenue stream fundamentally changes the economics for those dairy farms. As I noted several years ago, milk could become the byproduct of manure production if the farm is getting more profit from it than milk.

A lot has been made of high beef prices and the added incentive to cull unprofitable dairy cows. While that is true to a point, it is only part of the story. For farms that are downsizing or exiting, the high beef price is definitely welcome. But for farms wanting to replace those cows, the cost of a replacement heifer is quite expensive, so they might keep the older cow around a bit longer. In addition, for areas with base-excess programs, some farms are taking on additional cows and base as they look ahead to future expansion. This keeps the cows in production.

The other income stream impacted by high beef prices is one rarely discussed — the value of calves. This is a new and overlooked factor in dairy farm finances. In the past, farms sold dairy calves into the beef market for little to no money. But in recent years, more farms are using beef bulls on the lower end of their herd, up to half to two-thirds of their cows. In the current market, those beef-dairy cross calves are worth substantially more than straight-bred dairy calves. As an example, a 1,500-cow dairy breeds their top third (500 cows) to dairy for replacements and their bottom two-thirds (1,000 cows) to beef bulls. That beef-cross calf is worth $500+ right now versus $200 for a dairy calf. Those 1,000 calves bring in $300,000 in extra revenue. On a hundredweight-of-milk basis, that is over $0.75! Or consider the value of the dairy calf just a couple years ago when they were $25-$50 per head. The extra income is $500,000 in this example.

Another under-reported aspect of dairy farm finances is that many farms entered 2023 with strong balance sheets after a very profitable 2022, and in some cases 2020-21. This allowed farms to pay forward expenses and provided a cushion for lower prices this year. For some, the pot of extra money is now gone, and they will have to endure several months of negative margins. In recent weeks, I have heard of large dairies in several Western states losing $1 million to $2 million per month. Obviously, this is not sustainable, so the pace of contraction is expected to pick up as Q3 progresses. A common saying in dairy is that it takes longer to slow supply than you think it should, and that has been the case again this year.

Milk prices will increase in the coming months, and with substantially lower feed costs, dairy farm break-even levels will drop from the low $20s to the upper teens for most farms. With better margins forecast for 2024, milk production is expected to post near-average growth. There will be another downturn in milk prices in the future, and farms will endure another period of poor margins. However, in pure economic terms, each downturn takes longer to take out the marginal level of production as the cows and farms that need to be removed are stronger than the prior downturn.

The next three to five years will likely see an acceleration in dairy farm exits as farmers retire. On current trend, the number of farms could decline to near 15,000 by 2030. The farms that remain will be focused businesses that specialize in dairy production with multiple other revenue streams from the dairy. As a result, the old way of thinking about how dairy farm margins impact supply and demand will need to change, too.

Mike McCully is owner of McCully Consulting, South Bend, Indiana, and contributes this column for Cheese Market News®.