It was on his runs that Neville Ross first noticed cows were slowly disappearing from local farms. In 2017 most of the stock vanished from two farms. A year later they disappeared from a third Cambridge farm.

“Some places you realise there’s no animals – at all – for like a year.”

Neville’s not a farmer, he’s a cop and has been part of Waikato’s police force for 42 years. Despite being a detective sergeant, when the working dairy farms became ghost farms, it didn’t weigh on his mind. All three were owned by Fonterra. If it was a case of cattle-rustling or alien abduction, the multi-national dairy giant would have sounded the alarm.

He didn’t know stock was vanishing from other Fonterra farms around New Zealand, or that one day he and his wife Denise may have lingering doubts over his health and whether it was connected to what goes on at the empty properties.

You wouldn’t know it to look at him, but Neville’s on sick leave at the moment.

Neville’s always been fit, Denise says. He’s competed in triathlons, half Ironmans and he used to bike the 26km between the Cambridge lifestyle block they bought nine years ago and his Hamilton job. He’s never smoked and isn’t a drinker. His healthy lifestyle and current condition seem at odds. “He’s always been incredibly healthy … we’re always wondering why.”

With a grin, Neville says he’s not sick, but that his brain doesn’t turn on sometimes. Occasionally, while discussing the empty farm down the road, words slither away from him and Denise fills in the gaps.

The farm is Buxton Farm and aside from a lack of stock and a smart-looking Fonterra “Dairy is life” sign at the gate which, among other things, warns of wandering stock, it looks like any other farm in the area.

There’s plenty of lush looking grass, fences and farm buildings. But it’s not really a farm any more, it’s a tip. Since 1994, Fonterra has been piping wastewater from the nearby Hautapu milk processing plant and dumping it here.

During peak production periods the Hautapu plant processes about 150 tanker loads of milk and uses between 6000 and 8000 cubic metres of fresh water daily.

Some of the water remains fairly clean and is pumped into waterways but the water used to clean the factory’s tanks and pipes contains cleaning products.

This water has to go somewhere. In 1968 it was irrigated on just one Fonterra-owned farm, but as milk production grew, and more water was used, more and more properties were irrigated, including Buxton Farm.

According to Fonterra, when managed well, wastewater can help grow grass which is used to feed cows and “provides us with a good circular model for nutrient management”.

But the reason cows have vanished from the farms is that their urine contains nitrogen. Factory wastewater also contains nitrogen from cleaning products, such as nitric acid used to clean the vats and pipes. Add the nitrogen from the wastewater to the nitrogen from cows’ urine and you get a higher load. What isn’t used by grass can start a slow seeping journey into ground water. Underfoot, and invisibly, this polluted water can move beyond a farm’s fences. Removing cows from the equation means more wastewater can be spread on the land.

These sorts of farms, where stock is removed and the grass is cut and carted elsewhere as feed, are referred to as ‘cut and carry’ farms. Fonterra says 16 farms it has consents to spread wastewater on are predominately cow-free, cut and carry farms – or as it puts it – farms whose primary use is “nutrient management”.

For a long time, neither Neville or Denise knew Buxton Farm was used to soak up wastewater from the local dairy plant. After all, it looks just like any other farm. It wasn’t until last year they finally discovered what Fonterra was doing at Buxton Farm, after the community fought Fonterra’s proposal to build a wastewater treatment plant on the property.

The prospect of an industrial plant with huge ponds in the rural setting didn’t go down well with the locals, who felt it might be better located in industrial-zoned land closer to the Hautapu factory. Fonterra has since withdrawn the proposal and is investigating other locations for the plant, but before the U-turn, locals organised community testing of bores close to the farm to see what condition their water was in. That was the first Neville and Denise realised there could be problems with their water.

When they first moved onto the property in 2010 while Neville was building their house, they both drank bore water. When construction was complete, Denise switched to drinking rainwater but Neville didn’t; he thought the bore water tasted better.

Fonterra had been testing the bore water of some locals, although there had been an 18-month wait to have results sent to them. The company never offered to test Denise and Neville’s water because Fonterra thought the flow of ground water from Buxton Farm went north and the Ross’s farm lay to the west.

So, it was 10 years before the couple got their first test results. “We got our tests back at that stage at 11.9, which was really high. I still had no idea about what that meant.”

Nitrate in drinking water

You can’t see the nitrate-nitrogen. It’s colourless, odourless and tasteless and it can’t be boiled away – in fact boiling will only concentrate the levels.

The amount allowed in drinking water in New Zealand is 11.3 milligrams per litre (mg/L). It’s a level suggested by the World Health Organisation to avoid ‘blue baby syndrome’, a fatal condition caused by consuming too much nitrate during pregnancy, or via bottle feeding.

The nitrate reduces the ability of red blood cells to release oxygen to tissues. Putting it simply, it can suffocate a baby, turning them blue.

There’s only been one fatal instance recorded in New Zealand but it’s a health concern taken seriously in parts of Canterbury. Midwives there advise people living in areas known to have high levels of nitrates to get their bore water tested and to use bottled water during pregnancy and for bottle feeding if results show a high level.

However, another potential health risk has emerged. Some studies have shown a significant association between nitrates (at levels as low as 0.87mg/L) in drinking water and colorectal cancer.

Other evidence, although not as strong, shows a possible association between nitrate in drinking water with bladder and breast cancer, thyroid disease and birth defects.

Denise’s shock

Denise was in the local community hall, packed with neighbours concerned about Fonterra’s wastewater treatment plant proposal, when she first found out about nitrates and the association with cancer.

“I was in shock … Neville – two years ago – was diagnosed with brain tumour cancer, which is terminal.”

At 11.9 mg/L, their results were above New Zealand’s standard and well above the levels associated with colorectal cancer.

“Just the thought that could be part of the reason why Neville’s sick, it really upset me.”

He has glioblastoma multiforme, an aggressive brain cancer and has been through chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Neville’s doing ok at the moment – he’s in remission – but earlier this year Denise described his condition as “pretty crook”.

Unlike colorectal cancer, brain cancer hasn’t been linked with nitrates in drinking water, but that’s not enough to put Denise’s mind at rest.

“If it’s not [the cause], well, that’s life and it happens. If it is that, that’s bad and we need to do something about it,” she says.

Neville and Denise aren’t anti-dairy or anti-Fonterra. They both see the company as being an important part of New Zealand’s economy and say the company has been helpful since the problem with their water quality was discovered. However, after looking into what’s in the wastewater being dumped next door, Neville’s concluded it “is a bit untidy in regards to human beings” and wonders if there’s a better solution.

Denise says there’s been deaths in the area due to cancer in recent times, and while there’s no suggestion they are due to the ghost farms, she can’t help but wonder. Neville worries about the rest of the neighbourhood too.

“There are a number of young families which live in and around this area.”

Fonterra has given Neville and Denise a filtration system to remove the nitrate from their water. In total, the company has supplied 38 water filter systems to properties near the Hautapu factory because of groundwater contamination.

Fonterra had a new option for dealing with the factory’s wastewater, which didn’t involve spreading it on local farms, but it pulled the plug on it in October. The project would have seen its Hautapu wastewater managed by the municipal system. Minutes from a Waikato District Council meeting throw some light on the reason Fonterra bailed out. “Factors (including cost impact to Fonterra and uncertainty of cost, commercial arrangements and delivery timelines) led to Fonterra deciding to withdraw from the project…”

Fonterra gave timelines as the reason.

“We want to have a solution in place as soon as we’re able to and are targeting completion of our wastewater treatment plant by 2025, whereas the council plan had longer time frames.”

The bigger picture

It’s not just Cambridge’s picturesque lifestyle blocks which have Fonterra-supplied water filters because of wastewater spreading. People in the dairy-intensive Canterbury have been given new filters too. But are there some who, like Denise and Neville, have no idea they’re living near a ghost farm where dairy processing companies such as Fonterra (the smaller dairy companies do the same) disposes of wastewater.

Often, these farms are irrigated with wastewater for decades and hold resource consents to irrigate for decades more. Consents may have been publicly notified when they were first granted, but over the years new neighbours may have moved into the area.

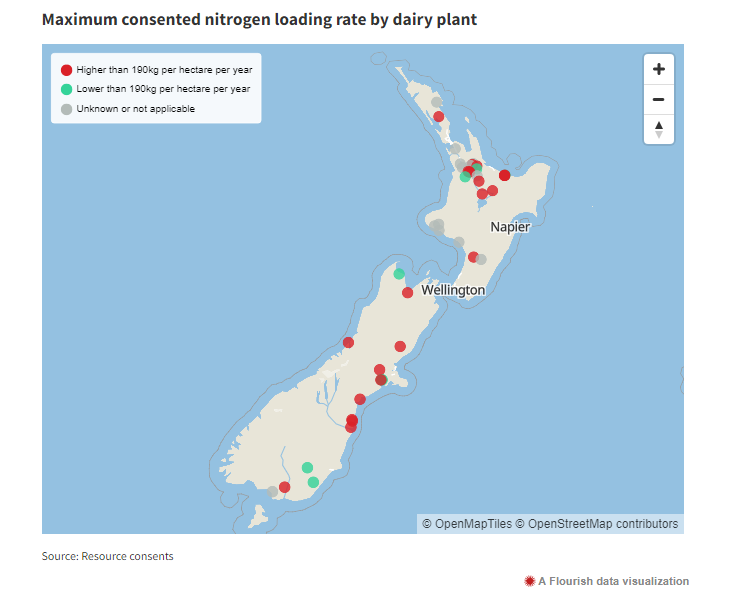

There’s something else worth noting about some of these consents. The amount of nitrogen that can be spread in the wastewater is often far higher than the new freshwater rules will allow farmers to spread on grazed land as fertiliser (190kg per hectare per year of synthetic nitrogen). Unless the wastewater is more than 5 percent nitrogen it’s not considered fertiliser. Because the wastewater farms hold resource consents for disposal of waste products, they will be able to sidestep the new rule which comes into play in July and continue to spread as much as their consent permits.

When asked if it planned to reduce the amount of wastewater spread to the 190kg of nitrogen per hectare per year farmers will be limited to using, Fonterra’s response was it would react to rule changes as required:

“In all our operations we work within the guidelines set by the councils. When changes are made, we adapt our operations to fit.”

But the company does say it has major spending planned over the next decade, with $400 million earmarked for upgrades to wastewater plants at their Edgecumbe, Whareroa, Maungaturoto, Te Awamutu, Longburn, Reporoa, Kapuni, Clandeboye and Hautapu factories.

Fonterra also says it already aims to reduce the amount of nitrogen in the water before it reaches farms by limiting the amount of milk residue in it and using dissolved air filtration or biological treatment plants to clean the wastewater.

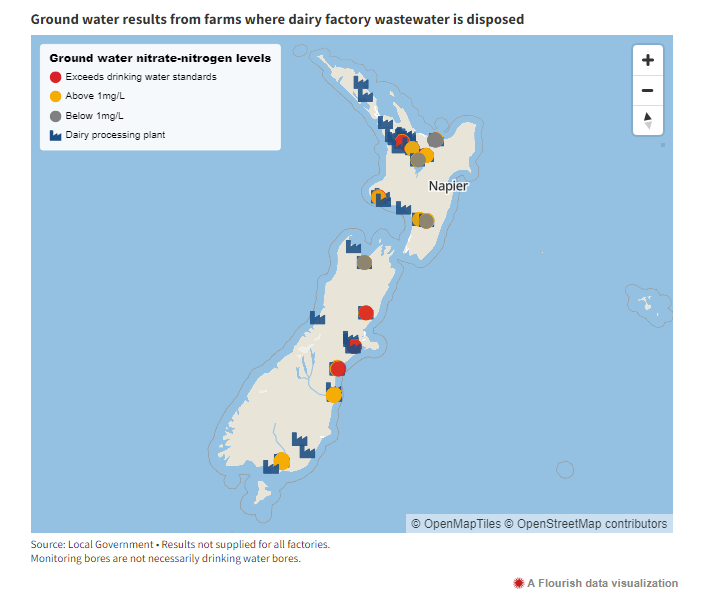

In some cases the differences between the new synthetic nitrogen cap for fertiliser and the amount of nitrogen the dairy companies are allowed to spread in wastewater are eye-watering. The current highest consented amount is in Canterbury. Fonterra’s Clandeboye plant is allowed to spread up to 600kg of nitrogen per hectare per year. It’s currently not spreading this much, but Environment Canterbury’s 2020 nitrate risk map links past wastewater irrigation with high levels of nitrate-nitrogen in the area. One survey describes a “contamination plume” and notes 53 wells, mostly near the Clandeboye dairy factory and Seadown fertiliser storage facility, exceed drinking water standards for nitrate-nitrogen. Fonterra has supplied two Canterbury homes with water systems because of nitrate in the ground water, and another house with a UV filter.

In the Waikato, Fonterra’s Hautapu plant has a resource consent to spread up to 500kg per hectare per year on Bruntwood farm and 400kg on Buxton and Bardowie farms. Maximum results from monitored bores show a reading of 17.80mg/L for Bruntwood farm, 18mg/L for Buxton farm and 26.8mg/L for a bore on Bardowie farm.

In Reporoa, wastewater has been spread for decades and at one point up to 800kg of nitrate-nitrogen was allowed, this has dropped to 420kg. The highest average reading from the 2017/18 fiscal year from a bore in the area is 18.7mg/L.

RNZ’s efforts to gather resource consents and monitoring results from wastewater farms nationwide found some consents don’t require monitoring. For those that do, most show levels of concern in some, but not all the bores monitored for many of the farms where water is spread.

Even if monitoring is a condition of resource consents, most don’t require a reduction in the amount of wastewater spread if the ground water is affected.

Beyond the farm gate

Alison Dewes knows a bit about cows, dairy farming and water. She’s the fourth generation of her family to dairy farm, worked as a vet for several years and is an ecologist and staunch advocate for water quality. Currently she consults on sustainable farming practises.

She thinks regional councils have shown a “cumulative regulatory failure”.

“Although councils might argue they’re not necessarily responsible for public health, they are because of the duties under the RMA [Resource Management Act] to protect life support capacity of the natural resources for future generations.”

Dewes’ has been following the decline in New Zealand’s water quality.

In a pristine New Zealand environment, before cows, fertiliser and wastewater, the nitrate-nitrogen level in ground water would have been around 0.25mg/L, according to a paper published in 2012.

Farming, an increasing population and industry quickly changed that. Stats NZ and the Ministry for the Environment’s most recent ground water quality report shows over a five-year period the median result from 75 percent of monitored sites exceeded 0.25mg/L across rural and urban landscapes.

The practice of spreading dairy factory wastewater on farms has been around for as long as she remembers. It was the impact on animal health which first raised concerns for her.

“As a veterinarian I would see it firsthand, where there has been continued application of the wastewater because the cows always had common metabolic problems. This included milk fever prior to calving, so you would often be on those farms around calving time and early lactation.”

She’s also seen the impact of nitrogen in ecosystems and drinking water and even though wastewater farms are only one part of what’s increasing nitrate-nitrogen levels in ground water, Dewes feels it’s important to raise the issue.

The message – what happens on a wastewater farm doesn’t stay on a wastewater farm – is something she’s eager for the public to understand.

“Activity inside a farm gate connects to shallow aquifers, into receiving headwaters, spring fed streams and rivers, and effect the common ground, which is our rivers, and our shared amenity, and also our drinking water sources. Until people can join those dots in their head, we’re not going to get change.”

As well as not allowing wastewater to be spread on the type of soil she describes as “leaky”, there are three main areas where she thinks improvements could be made.

Firstly, most of the monitoring of ground water quality, which is done as conditions of resource consents, is done by companies themselves – it should be done by the council. Secondly, sometimes the monitoring sites are chosen by companies and may not be in the best locations. Finally, there’s a lack of transparency.

Monitoring results are usually supplied to the council, but not always readily available to the public unless specifically requested. People may not know the farm down the road from them has a ground water problem.

Environment Canterbury is open about the fact land use has impacted the quality of ground water and because nitrogen can take years to move through water problems won’t be disappearing anytime soon. The council’s website says in some cases “we can expect the situation to get worse before it gets better”.

Community water supplies are regularly tested, but the responsibility for private bores lies with owners.

When it comes to monitoring the effect of wastewater spreading on farms, it says its job is to monitor that monitoring is being done by the consent holder not do it itself.

Environment Canterbury’s Director of Science Dr Tim Davie says this ensures the cost of monitoring is covered by the consent holder, not ratepayers.

Waikato Regional Council holds the same stance. Its job is to monitor monitoring.

“Waikato Regional Council undertakes site inspections, audits compliance with conditions to ensure the data is reliable, and where necessary holds consent holders to account,” says Waikato Regional Council resource use acting director Brent Sinclair.

Both councils publish data about nitrate-nitrogen concentrations through regional ground water quality monitoring programmes. This data does not necessarily include the results of consent monitoring.

“The data Fonterra collects is to assess the impact of its operation and is available on request to anyone who is interested,” Sinclair says.

The new limit of 190kg per hectare of synthetic nitrogen is something which will “no doubt” be taken into consideration by independent commissioners when the currently expired resource consent for Bruntwood and Bardowie Farms is renewed, he says. Documentation lodged by Fonterra as part of the process suggests a new strategy will see a reduction of nitrate-nitrogen levels from 11mg/L to between 5 and 8mg/L.

Both councils are aware of the studies linking nitrate in drinking water with colorectal cancer and are supportive of further research but say they operate with guidelines which have been sent at a national level.

When asked if it was concerned about cancer and nitrate, Fonterra says that the health and wellbeing of the New Zealand public is important to it.

“We keep an eye on the science as it develops. We rely on experts in this field to set legislative limits that are best for the public and the environment and we work within these.”

But Denise wants Fonterra to “do it right” when it comes to wastewater.

“I understand business and that it has to be viable, but sometimes putting in that extra bit – and it may be a lot of extra bits – is actually a better idea when you’re in the neighbourhood. Just look after us. We do think Fonterra is incredibly important. We are a farming country. We do want them to stay and not to go, but just do it tastefully, and do it properly.”