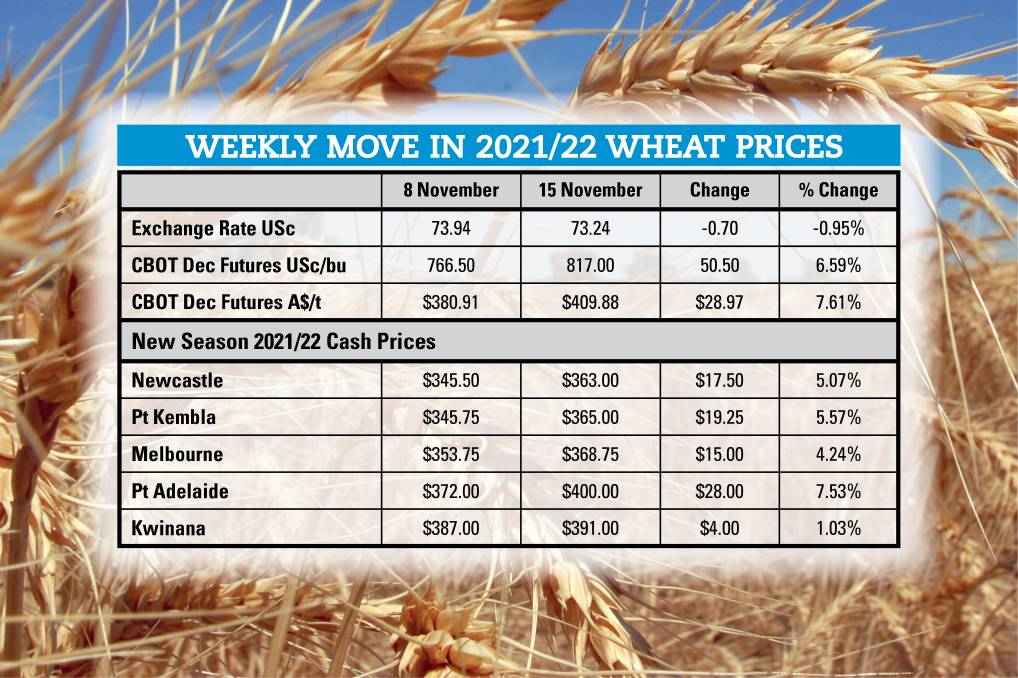

Wheat prices have surged again, triggered initially by last week’s USDA Report that reduced global stocks by 1.4 million tonnes, which was a little more than expected.

The tightness in wheat stocks is greatest within the major exporters. Against consumption, the stocks to use ratio for the major exporters is at its lowest for about 25 years. Stocks themselves are as low as they have been since 2007/08, which is the last time we saw wheat prices approaching current levels in $A terms.

There are multiple factors providing price support though, including dry conditions in regions with newly planted winter wheat crops, and further export restrictions being talked about for Russia. We can add harvest rains in Australia to that mix as well.

In the EU prices have hit their highest levels since 2007, with expectations that export volumes will have to slow as exportable supplies decline.

High wheat prices are also being reported from the Black Sea, with prices at 13-year highs. That is no surprise given that wheat prices are high everywhere, but for Russia, this is a catalyst for looking at restricting exports with quotas, and for tweaking their export tax regime to increase taxes to try to limit exports and reduce domestic wheat prices.

The other factor supporting Black Sea wheat prices is a period of dry autumn weather impacting newly planted winter wheat crops in Russia and Ukraine. Some analysts are saying that it is the driest autumn in 20 years in Ukraine, and winter wheat planting has stalled with 94 per cent of the planned crop planted.

There is an expectation that Ukraine’s winter wheat acreage will fall short, and may decline year on year rather than increase as originally forecast.

In the US there are similar issues with their newly planted winter wheat crop, with crop condition ratings falling, and slipping below those of last year.

While conditions for the 2022 northern hemisphere crops are in the mix for supporting the current price levels in international futures and physical wheat markets, the reality is that crop conditions in autumn are not strongly correlated with final yields and production in the following summer.

For example, planting conditions in Ukraine were not ideal in 2020, and the acreage planted was down, but production went from 24.9mt in 2020 to 32mt in 2021, because a mild winter more than compensated for the reduced planted area.

Here in Australia, the focus is on harvest rains now extending across the country. The mild spring temperatures and spring rains have seen production estimates lift to potentially record levels, but the concern is that weather damage will see deliveries of much-needed milling grade wheats decline.