COQUILLE, Ore. — For about a year, Oregon dairy farmers Mike and Lisa Miranda asked themselves: “Why are we doing this?”

There was no good answer.

Milk prices were the same as they were in the early 2000s, when they started in the business. But costs to run the operation had doubled, and they had to contend with mounting government regulation.

They stopped milking on April 28 and sold their 250 organic cows and heifers to two nearby dairies.

Courtesy of the Miranda family

When asked if it was a difficult decision, Lisa gave a resounding “Nope.”

But there was more to the decision than economics. They both grew up on dairy farms in northern California and come from long lines of dairy farmers. Mike’s dairy roots trace back to the Azores, and Lisa’s to Denmark. They raised their two children on the dairy farm and love the business.

“I miss hearing the milk barn run. I got up at 1 o’clock and pushed cows in every day and made sure the milkers were here,” Lisa said of her early morning routine.

But it came down to this: Why deal with unprofitable milk prices, paperwork and regulation when they had other income?

“We do a lot of custom feed in the spring and summer, and it just kind of grew the last few years,” Lisa said.

In addition to growing feed crops for other producers, they buy, resell and deliver feed — and all the income from those businesses was going into keeping the dairy running.

“If we didn’t have the dairy, that money would be going in our pocket,” Lisa said.

Other factors also played into their decision. Being organic meant as many as 10 inspections a year. Keeping up with all the regulatory paperwork was just a struggle, she said.

“Every time you turned around, there was another inspection,” she said.

Burdensome state regulations were also a factor.

“Every time we have a legislative session, we have more regulations,” Mike said.

More regulations always mean more business expenses, Lisa said.

The overtime regulation alone is hurting farms — and farmworkers, they said. It was supposed to help workers, but it’s hurt more than it’s helped. It limits worker income, forcing many to look for a second job, Mike said.

‘Killing family farms’

“It’s just all these regulations. There’s something being thrown out at animal agriculture all the time. Basically, they’re running us out of business … they’re killing the family farms,” he said.

Courtesy of the Miranda family

The bigger farms have someone on staff to handle all the regulatory paperwork and red tape, he said.

Their son, Matt, works in the operation but doesn’t want to deal with the growing number of headaches. He doesn’t want to dairy, and they don’t want him to have to deal with the stress.

The Mirandas also needed to upgrade their milk barn and manure storage facility.

“Knowing we needed to make capital expenditures and our son didn’t want to dairy, we just asked ourselves, What are we doing this for?” Lisa said.

Trending lower

The Mirandas’ story is common in the dairy industry. More than 1,900 dairy farms exited the business in 2021, leaving 27,932 farms in 2022. That number will be even lower in 2023, as dairy dispersal sales take place across the U.S.

Though the dairy industry has lost more than 77,000 farms since 2000, the number of dairy cows has remained consistent as other farms grow larger in an effort to achieve efficiencies of scale. Production also is increasing as each cow produces more milk, according to USDA.

The number of dairy farms in the U.S. declined last year at a similar rate as the year before, said Alan Bjerga, senior vice president of communications for the National Milk Producers Federation.

“Consolidation has been a decades-long trend in the industry that’s been expected to continue for many of the same reasons it always has — the economies of scale offered by larger farms and the fact that many dairy farmers who are ready for retirement and don’t have a successor to take over will sell to an already existing operation,” he said.

The trend could accelerate this year, said Rick Naerebout, CEO of the Idaho Dairymen’s Association.

The typical cost of production in Idaho right now is $21 to $22 a hundredweight, while the milk price is in the $14s, he said.

“The losses our dairymen are experiencing right now are approaching 2009 losses, which are the worst on record. We have definitely seen an increase in dairymen leaving the industry,” he said.

Idaho has lost 10% of its dairies in the last year, dropping from 400 to 360, he said.

“As the financial aspects of dairying get worse this year, we expect to keep that pace, if not increase it. I expect you’ll see an uptick in dispersals and even bankruptcy,” he said.

Record feed costs are the biggest factor in increased expenses for dairymen, but labor, energy, interest rates and the other inflationary costs are also factors, he said.

Finances are always top of the list when dairy farmers exit the business, but other factors are making their way up that list, he said.

“First and foremost, we have a generational issue on our small and medium-sized dairies. The next generations have watched their parents work so hard to keep things afloat that they often seek other career paths so they can have the quality of life as adults that they desire,” he said.

He knows because that’s the route he took almost 25 years ago, and it was a big reason his family sold its operation in Michigan and moved to Idaho.

“It is far easier to work for dairymen than to try and be a dairyman. If you are the main source of labor and management, you don’t get paid vacation, weekends off or a company-matched 401k,” he said.

Increased expectations from the supply chain are also a factor. The increase in record keeping and audits surrounding animal husbandry, worker wellbeing and sustainability, along with the growing expectations to reduce greenhouse gas emissions all make it that much less appealing to stay in the industry, he said.

“Larger facilities are able to hire staff to fulfill these expectations, but if you are a small to medium dairy, all this falls on the owner’s lap to manage and execute. It is not why they got in the business,” he said.

“Dairymen are typically ‘cow people’ and they dairy because they like working with cattle, not to fill out reports to determine their GHG footprint or to market green energy,” he said.

Regulatory burden

The Oregon dairy community has been hit hard the last few years, said Tami Kerr, executive director of Oregon Dairy Farmers Association.

The state lost 25 dairy farms in 2022, and 101 have gone out of business in the last 10 years, she said.

High feed costs, labor shortages, additional regulations, milk checks that don’t cover expenses, exhaustion and not seeing a future where things improve for the next generation are all factors. But the biggest factor is overly burdensome regulations imposed by the state, she said.

“Oregon is not a business-friendly state, agriculture is at a tipping point and sliding over the edge. Oregon needs to decide if they want to be an agricultural state,” she said.

The state has one of the highest minimum wages in the country, and overtime regulations for agriculture and paid family leave were implemented on Jan. 1, she said.

“To hire, and more importantly retain, skilled employees, producers are paying well above minimum wage and often providing housing and other benefits,” she said.

Dairy farmers also have to deal with heat and wildfire smoke laws and the Corporate Activity Tax, which applies to many items and supplies they purchase, she said.

“The impact of legislation is real; we are losing farms in record numbers,” she said.

California — the largest milk-producing state — has seen a steady decline in the total number of dairy farm ownership since 2009, although it has rapidly declined since 2015, said Anja Raudabaugh, CEO of Western United Dairies.

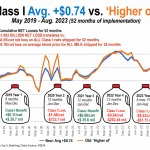

WUD

The state lost 60 dairies in 2021 and 325 between 2015 and 2022, according to USDA.

“This is a concerning trend and one that the California dairy industry should be on total fire about. Increasing regulatory uncertainty, coupled with drastic weather boomerang of drought and flood, will only exacerbate this trend,” she said.

Auction uptick

Auctions are all seeing an uptick in dairy dispersals, especially for this time of year, Dave Macedo, owner of Tulare Sales Yard in California’s Central Valley, said in late May.

“People are just tired … there hasn’t been three or four decent years since 2009,” he said.

It’s just tough to stay in business anymore, and they don’t want to keep throwing good money after bad, he said.

“There’s just not much to make them want to get up in the morning and milk a cow, except they love what they do,” he said.

“I’ve seen guys over the last 10 years break themselves trying to feed their cows and keep their business going,” he said.

But unlike in the past, dairies aren’t being forced to sell — they’re choosing to, he said.

“Guys just said, ‘I’m not going to continue to do this and not make a living,’ they’re beat up enough,” he said.

His clientele tells him a significant amount of money is being lost on a daily basis, and he thinks that’s pretty much the case in the West and Southwest.

Milk prices plummet

Milk prices were high last year, in the mid to upper $20s a hundredweight, but farmers were paying $400 to $500 a ton for hay. Now milk prices are tanking to the mid-teens, he said.

Producers were kind of waiting to see how things would go this year, and it’s shaping up to be not so good, he said.

A couple of other auctioneers in the West — who didn’t want to be quoted — told Capital Press they were also seeing an uptick in dispersals, saying feed costs, milk prices, regulations, taxes and a lack of interest by the next generation were all factors.

Fatigue a factor

There are a lot of factors in dairy farmers exiting the business. But the main one is fatigue from all the headwinds they’ve faced, even before the pandemic, said Hernan Tejada, University of Idaho Extension dairy and livestock specialist.

UI

The COVID pandemic threw a wrench in the dairy economy, and though government assistance programs helped dairies survive, they started to expire last year. The last one to help dairy producers ended in January, he said.

Milk prices were high last year, but so were feed costs. This year feed costs have come down a little, but milk prices have dropped rapidly, he said.

“I think many folks are worn out, (saying) ‘I can’t handle this anymore,’” he said.

It’s been a continuous, difficult situation. The government programs helped, but things have gotten tough again, he said.

“Now the folks who don’t have succession plans are tired,” he said.

Producers are aging and unless the younger generation is optimistic and committed, they can sell to producers who want to grow their operation, he said.

“There’s been too many difficult setbacks. … I don’t want to paint a dire picture, but it’s a reality,” he said.

Back on the farm

The Mirandas had milked cows in Coos County for 21 years, starting with a 26-head commercial herd in 2002. They transitioned to organic in 2004 and grew the herd to 250.

They would have liked to stay in the business they loved, but it was unsustainable and they had other options.

“We didn’t make the decision lightly,” Lisa said.

They would have had to milk 700 to 800 cows to stay in business.

“We didn’t ever want to be a big dairy,” Lisa said.

“Used to be you could milk 100 cows and raise a family,” Mike said.

It’s just not sustainable for a young person to get into the business, he said.

“We were dumping money from the other businesses to keep the dairy going,” he said.

Other dairy farmers don’t have those other businesses, and the Mirandas wonder how they’re staying afloat.

“A lot of them have used every drop of equity they have” to borrow money to keep the farm in operation, Mike said.

The Mirandas have more demand for their custom feed, and Mike has started hauling milk.

“It’s just a kind of different milk check,” he said.

They’ll keep the ground organic — with only two annual inspections — and they’re pasturing 70 beef cows.

“So we’re not working any less hours, we’re still working 365 days out of the year,” he said.

But there’s a lot less stress, Lisa said.

“Now we just go out and run our equipment, and we go home,” she said.

But selling the dairy cows has given them more freedom to do things like visit their daughter, Maegen, and family in Arizona.

“We can just pack up and go,” Lisa said.